A veteran’s guide to fundraising

When growing a business, money helps. Unfortunately, there’s less of it around these days. As interest rates rose around the world, global venture capital deal-value halved between 2021 and 2023 according to Pitchbook, while exit value was the lowest since 2017. Pickings are equally slim on the stock market. In 2022, there were only 45 initial public offerings (IPOs) in London, raising £1.6bn, compared with 119 issuers in 2021 raising £16.3bn. Last year was even worse, with only 23 IPOs, raising £954m.

None of this means that scale-ups can’t access the finance they need if they have the right business case for investment. Nor does scarcity of funds mean taking whatever you can get: if anything, now is the time to exercise discernment in where you get the funding for your next stage of growth, and from whom.

The right financing route will depend on the maturity of your business, its capital requirements and your personal preferences. In this article, we zoom in on private investment, with advice from GX veterans who’ve been through the process.

FINDING PRIVATE INVESTORS

Private investors can supercharge growth with seed (concept), angel (early-stage) and VC (scale-up) funding, although some private equity companies and family offices will also consider high-growth propositions. Alongside capital many of them bring invaluable expertise to the table, helping scale-up founders with industry specific or general management problems alike. When looking for investment, it pays to be methodical.

List the funds or investors that cover your stage, industry and geography, and identify the correct partner at each firm. “Find a warm introduction, even if it’s someone you know on LinkedIn, because the likelihood of success from cold calls is very low,” advises Tripledot Studios co-founder and CEO Lior Shiff. He raised $202m for the mobile game developer across one seed and two VC funding rounds between 2018 and 2022, the latest giving it a $1.4bn valuation.

Think carefully about the sequencing of approaches too. No matter how strong your deck is, the first few pitches will be a learning curve, so be prepared to lose those. “Managing the timing is really important, because ideally you want a few interested investors at the same time to create some competitive tension,” Shiff says.

If all this sounds time consuming, that’s because it is. But don’t think it’s something you can easily outsource, says Huel CEO James McMaster, who helped the nutrition business raise £40m of investment from Highland Europe and later Sabrina and Idris Elba across two VC rounds in 2018 and 2022.

For early stage companies, investors are betting on the founder as much as on the business, so having an advisor do the pitching won’t go down well. Even at the VC stage, using a corporate finance firm can be more time-consuming than doing it yourself.

“Potential investors at any stage will want to ask an unlimited number of questions before they invest, yet the company wants to minimise the time they spend on this and maximise their time running the business. Saying no to investors can be scary at first, but if you believe they have enough information then you’ve got to push back,” McMaster adds.

Above all, show perseverance, says Julie Lavington, who with co-founder and co-CEO Ali Hall raised £2m from 40 angel investors to launch womenswear brand Sosandar in 2016. “There will be people who doubt you every step of the way, saying it can never be done. But there will be people who believe in you too, you’ve just got to find them.”

SEALING THE DEAL

No matter how flattering it may be, avoid the temptation to accept your first offer. Lavington and Hall, for instance, rejected three individual investors who offered to meet the entirety of their £2m angel financing needs, as it would have cost them control of the business.

“Choose your investors carefully because they will become your partners. Make sure you share the same values, ambitions and goals, with alignment on what a good outcome looks like,” says Shiff. For example, exiting at $50m may be a great outcome for a founder, but not so for a VC if it only gives them a 2x return.

They may push for continued growth at a much higher exit value, even if that risks the business crashing and burning.

Have upfront conversations about their exit horizons too – are they willing to stick around for 15 years, or do they want to be out in two? Will they be able to provide additional capital in future rounds?

“Spend time with potential investors outside the office, such as in a restaurant or bar. Everyone is a bit more themselves and it’s easier to see how you get on. Another helpful sign is how long the people who would actually be working with you have been at the VC business and what is their employee turnover rate. It’s much better to have the same team with you the whole way through the investment,” McMaster adds.

Lastly, consider carefully the rights and preferences you’re giving away. These determine who gets what when the company floats, sells or shuts down. For instance, Shiff says that it’s fair to offer 1x non-participating preferences, where investors are guaranteed the higher of their equity share of the proceeds or their money back, before any other proceeds are distributed.

But he cautions against things like 2x or 3x participating preferences, where investors are guaranteed multiples

of their initial investments before the remaining proceeds are divided, plus their share of those proceeds.

“Try not to be greedy. I’ve seen lots of companies making the mistake of trying to maximise valuation in exchange for giving these rights, and then they sell for lots of money but the founders themselves end up with nothing,” Shiff explains. If you do decide to offer generous terms, remember also that you will almost certainly need to offer the same rights and preferences to investors you onboard in subsequent rounds.

DON’T BE DAUNTED

Raising growth capital can make or break your business. Doing it for the wrong reasons, at the wrong time, or with the wrong partners can cause more harm than good. Get it right, though, and the rewards can be enormous, particularly for high-growth companies in a race to grasp fast-passing opportunities.

Daunting though the process may be, particularly for first timers, keep a level head and focus on the fundamentals. As Shiff says, “If you build a great business, you will find ways to monetise it.”

What are the alternatives?

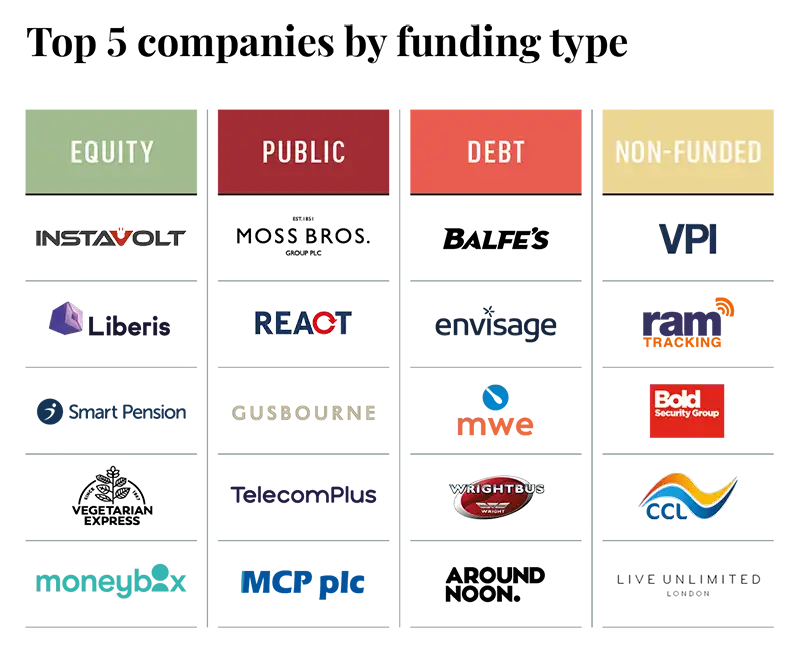

Private investment can transform a business, but it inevitably comes with some loss of control and dilution of a founder’s equity. It’s important to consider the alternatives fully before taking the plunge.

BOOTSTRAPPING

You could grow using your own cash flow. This has definite pros and cons, says Shiff, who bootstrapped

his first business before changing tack, taking angel funding for his second firm, and seed and venture funding for Tripledot.

“I felt that bootstrapping our first company made it too conservative. In a fast-growing ecosystem timing is really important, but we had to be very cash-flow aware and that slows you down,” Shiff says.

“The flipside is you don’t get diluted, and you also have flexibility to change without needing to explain it to anyone. I remember during a long drive with my co-founder, we decided to totally pivot the business. If we’d had investors on the board, that decision which took one hour would have probably taken a month.”

DEBT

If you want to grow faster but still don’t want to surrender shares, debt financing is another option. It still involves sacrificing some control – your bank will want consulting on major decisions – but it is generally cheaper than equity. The obvious downside is that you have to pay the money back, which means you also need to be profitable.

FLOATING

Lastly you could float on the public markets. This is more common for mature companies, but some scale-ups prefer it. Sosandar listed on small cap index AIM only a year after launch through a reverse merger with a cash shell company, as opposed to an IPO.

Co-founders and co-CEOs Julie Lavington and Ali Hall raised £5.3m in growth capital from the transaction, but the fact that it made them a plc had its appeal too. “Sosandar is a very democratic business. We felt that presenting to multiple big investors on a regular basis would let us keep that way of working, rather than having one person sitting at the end of the table making all the decisions, which could have happened with a private investor or going through the VC route,” Lavington says.

Other advantages of going public are credibility and ease of access to liquidity through secondary share issuances. On the flip side, plc investors usually have a lower risk appetite than VCs, and for smaller businesses the levels of capital raised will generally be lower.